Student Press Law Center provides valuable information to students and their teachers

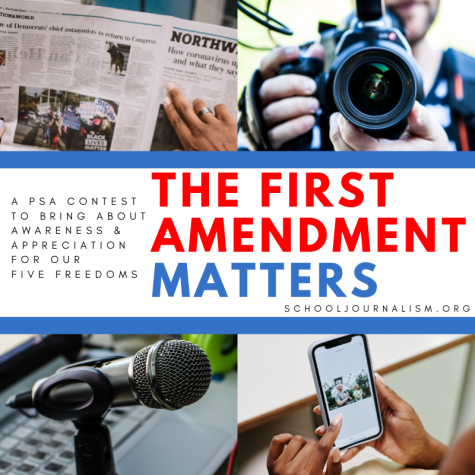

The Student Press Law Center has been a critical resource for high school and college journalists and their advisers since 1974. The SPLC is “the nation’s only legal assistance agency devoted exclusively to educating high school and college journalists about the rights and responsibilities embodied in the First Amendment and supporting the student news media in their struggle to cover important issues free from censorship,” according to their website.

The SPLC provides legal advice and educational materials for student journalists and their advisers. The agency also operates the Attorney Referral Network, a group of about 150 lawyers located across the country who provide free legal representation to students in their areas when necessary.

Frank LoMonte, SPLC’s executive director, said it is important for high school teachers to be informed and up-to-date on student First Amendment and press rights. The SPLC has a wide array of resources that can help teachers and student not only educate their district, but also themselves, on their rights.

The legal request form is an easy way for student journalists and their teachers to submit non-urgent media law questions and concerns to the SPLC legal staff.

The public-records letter generator allows anyone to obtain access to public records maintained by state or local government officials.

An assortment of legal guides provide information on a range of topics, from press freedom and censorship to libel and privacy invasion.

There are many resources designed specifically for use in classrooms, including online quizzes and presentations, handouts and lesson plans.

The newest feature that SPLC is debuting for this fall, in partnership with Education Week magazine, is called “On the Ed Beat,” which will provide story ideas that students can localize for their community’s readers.

“We are living in a time of obsessive image control among schools, and the pressure to censor is greater than ever now that schools are so protective of their Google results,” LoMonte said. “Image control is never, ever a lawful reason for a public institution to censor a story, and it’s by far the most common reason that’s cited when a student or teacher calls the SPLC hotline. ‘Making the school look bad’ is the single most common rationale cited when schools censor, and teachers need to be aware that denying the public candid information about unsatisfactory conditions at the school would never, under the First Amendment, be regarded as an educationally legitimate justification to censor.”

About 2,500 student journalists, teachers and others contact the SPLC each year from all 50 states and the District of Columbia, according to the SPLC’s website. LoMonte said the most commonly asked question involves republishing copyright-protected materials from the Web.

“The rule of thumb on any question about the reproduction of copyright-protected materials should always be whether the use of those materials in your publication serves as a replacement or substitute for viewing the creator’s original work,” LoMonte said. “If you play 20 seconds of a Katy Perry song with a newscaster talking over that song as she’s covering the Katy Perry concert, obviously nobody is going to use that snippet at a dance party in lieu of actually buying the song. But if you cross the line into playing the majority of the song purely for entertainment or amusement purposes as opposed to a necessary aid in your storytelling, then you are on much shakier ground to defend ‘borrowing’ the song as a fair use.”

When it comes to publishing photos found on social media, LoMonte said his advice is to “rely on social media only as a last resort and be scrupulous about verifying identities or at least level with your readers if you have any uncertainty about authenticity.”

LoMonte said school districts frequently fail to keep pace with what state law requires regarding student press rights.

“Oregon and Colorado have had student press-rights laws on the books for years, but their school-district policies have largely failed to keep pace with what state law requires, and it may become the teacher’s role — ideally, with her students taking the lead — to educate the district about where its policies are legally deficient,” LoMonte said.