Creating a Deeper Understanding of the First Amendment With a PSA Contest

The need for greater knowledge and understanding of the First Amendment is vital to our democracy. If this instruction does not occur in our classrooms, where is it taking place? In social media forums where misinformation and disinformation run rampant and unchecked, or within partisan realms where it is adapted to support political leanings?

Recently, the First Amendment Center of the Freedom Forum Institute announced the results of its annual State of the First Amendment survey. Out of approximately 1,000 adults, 21% could not name any of the five freedoms guaranteed by the First Amendment. According to a Freedom Forum release about the survey, “Of concern for First Amendment advocates is that more people agreed that the First Amendment went too far, rising to 29 percent from 23 percent in 2018 — emphasizing the importance of work to increase public understanding of how the freedoms of the First Amendment are applied in daily life, and how they help define what it means to be an American.”

SchoolJournalism.org’s First Amendment Matters PSA Contest is an effective tool to promote civic literacy in the classroom because it demands that students seek reliable and credible knowledge about the Five Freedoms it guarantees. How do I know? I assigned the project to all three of my journalism classes and was thrilled this spring when the PSAs of two groups were recognized: one as the Grand Prize Winner and the other as an Honorable Mention.

I used the PSA contest in my journalism classroom because it met several pedagogical objectives:

- It fostered a more thorough knowledge and understanding of the First Amendment.

- It challenged students to communicate that knowledge clearly and efficiently within the contest parameters.

- It required students to apply and effectively demonstrate their filming and editing skills.

- It facilitated a healthy sense of competition and excitement among the groups at a point in the school year when enthusiasm often wanes. The struggle is real when teaching mostly seniors in the final marking period.

The biggest challenge my students faced was understanding what the Five Freedoms look like in the real world and figuring out how to convey that to others. It is one thing to memorize the words of the First Amendment, but it is another to present what they mean, their true essence, in a clear, understandable way to the audience.

In preparation for the contest, I assigned the Student Press Law Center’s First Amendment Quiz and posed the following three questions for students to respond to our online class forum:

#1. How many did you get correct? Were you surprised by your results? Explain.

#2. Have you ever studied the first amendment in depth? If so, in what class?

#3. Explain why it would be beneficial for students to have an in-depth understanding of the First Amendment.

Most got at least 50% correct, but few earned much higher. Some did not recall learning about the First Amendment extensively, if at all. (Disclaimer: I often take into consideration that my very own students will swear they did not study something when I taught it to them, even though have the lessons to prove it.) Regardless, the takeaway is that even if it was taught or covered, it did not leave a lasting impression.

Many of my students were surprised with their results. One particular response caught my eye, from a junior who wrote that he was “kinda surprised by some of the wrong ones since they are against my beliefs.” In his case, personal values seemed to conflict with his understanding of how the First Amendment is and should be applied. This, perhaps, is a dilemma for many American citizens who may philosophically agree with the First Amendment “on paper” but may want to pick and choose the actual people, beliefs, and speech it protects.

The First Amendment Matters PSA contest demanded that students do additional research to ensure they knew what they were talking about. The 30-second time limit forced students to come up with creative ways to communicate what they learned. The “element of competition” and prizes offered an incentive that went beyond just a grade for completing the assignment.

I appreciate the support of all the contest sponsors who invested not only in the future of these students but in the future of democracy. I’m fairly confident that all participants can easily recall all five freedoms now (and some can impress me with their understanding of them). The project made a lasting impression, one that they will hopefully take with them as they continue their journey as democratic citizens.

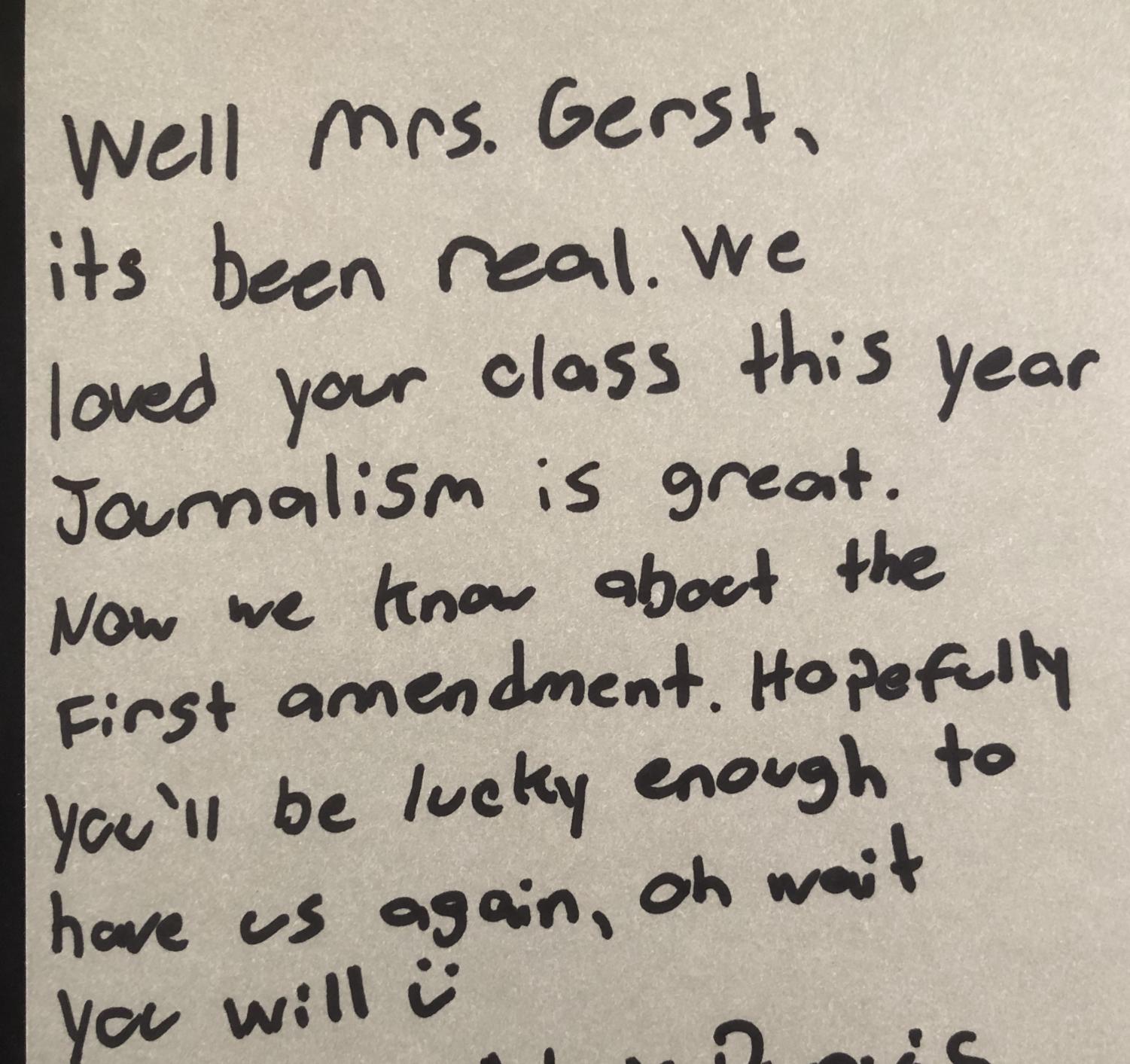

Perhaps the best testament to this came in a message a student wrote in my yearbook (included in this article). Mission accomplished.