Diagnosing Propaganda Techniques in Campaign Ads: Civic Discourse and Media Literacy

Presidential election years present ample opportunities for lessons in media literacy; depending on your outlook and your class dynamics, this is either exhilarating or terrifying. Either way, it’s necessary for us to play a role in helping students navigate the overwhelming messages that surround them.

As I have written about in the past, I’ve found rooting my media literacy lessons in classic rhetorical analysis has been the most successful in eliciting meaningful class discussions. By the time we start discussing propaganda techniques, we’ve been practicing understanding and analyzing the rhetorical situation and rhetorical appeals.

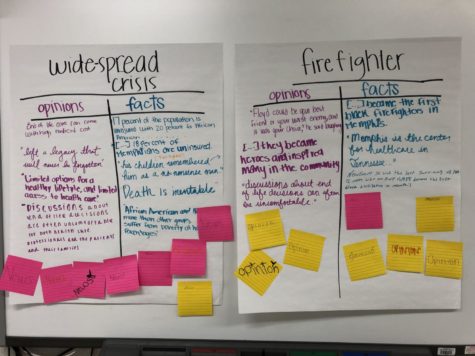

Years ago, I gave students a writing assignment that consisted of finding presidential campaign ads (both for and against candidates) and “diagnosing” the propaganda techniques. However, I quickly realized that setting them loose led to them finding ads of dubious origin, and the assignment just didn’t work. Since an integral part of the assignment was that I should not be able to tell whether or not a student likes or supports a candidate, I decided that this should be an in-class activity. It was important to curate the ads, and to practice having these discussions in a group. I noticed among my students an increased apathy and/or discomfort with having discussions about anything remotely political, even in a classroom environment, so this lesson has been helpful in both alleviating problems with the take-home assignment and helping foster a sense of comfortable discourse within the classroom.

Leading into this activity, students have been learning about and practicing rhetorical analysis, and in my English courses, we’ve also been practicing using historical American rhetoric, so they are primed for these conversations. Even without that kind of curriculum scaffolding, however, this lesson is easily inserted into a myriad of classes.

Handouts

Rhetorical Appeals Triangle (Ethos, Pathos, Logos)

Propaganda Techniques (From Propaganda Critic)

I give out a Propaganda Techniques handout, and have them look it over. Then, I play the following ads from the 2016 primary:

Hillary Clinton’s “Children” Ad

After each ad, I have students diagnose the propaganda techniques they find. Every once in a while I have to direct students to not make their political preferences obvious, but I’m consistently impressed with how well students stay on task and are able to critically analyze the ads. I sometimes give students background information (Hillary Clinton was criticized for not being feminine/motherly enough when she was first lady, and Ted Cruz was criticized for being an elite law professor) that helps contextualize the ads, but I only do so to help them fill in the rhetorical situation blanks that they might not be aware of.

Typically, I’ve also shown this clip of the first televised presidential debate between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon at some point in the semester. We talk about how TV has shaped political discourse, and how a debate like this is marked by civility (some students admit that they find it too boring and have come to desire the drama, which we reflect upon). We also point out that we know that that doesn’t mean the world or the candidates were actually civil off screen. We have to resist the temptation to imagine “the good old days” were actually that good.

In light of that, after we talk about propaganda techniques in more modern ads, I show some of these (AdWeek’s “10 Iconic Presidential Ads”) and have students continue diagnosing propaganda techniques. The “Daisy Girl” ad shows how fear is hardly a new propaganda technique in presidential campaigns. While this collection from the Museum of the Moving Image (“60 Years of Presidential Attack Ads, in One Video”) is excellent, I often have to pause and give some historical context for clarity. We see that the more things change (and certainly, the world of technology and media has changed), the more things stay the same.

I always want students to be able to engage with and critically analyze the news and entertainment media of their time, and for them to feel empowered by being able to do so. By giving students rhetorical analysis tools and historical context, we can help foster civic education and empowerment through media literacy skills.

Leigh Rogers • Sep 21, 2020 at 8:30 am

Love this! I’m so excited to use this in my English IV and publications classroom. What a great lesson.

Frank Baker • Jan 22, 2020 at 2:16 pm

Teachers may also be interested in my POLITICAL AD ANALYSIS WORKSHEET, perfect for use with students who are studying the symbolism, visuals and audio techniques in these ads. https://frankwbaker.com/mlc/political-ad-analyzing-worksheet/

Frank Baker author,” Political Campaigns & Political Advertising: A Media Literacy Guide”

https://frankwbaker.com/political-campaigns-and-political-advertising/