Empowering HS Journalists to Report on Race, Equality, and Social Justice

My name is Jane Bannester and I’m a teacher at Ritenour High School in St. Louis, Missouri.

On Aug. 9, 2014, Michael Brown Jr., an 18-year-old black man, was fatally shot by 28-year-old white police officer Darren Wilson in the city of Ferguson, a suburb of St. Louis. It happened on a Saturday. Our school began its first day of a new school year that Monday.

Ritenour High School was in the circle of protests that ran several weeks. It is only 13 miles from Ferguson, separated by an airport.

At first, our media publications (newspaper, online, radio news, and broadcast) tried to hide from the idea of covering this issue, but we soon learned it was not going away.

It had landed right on our front doorstep.

Our students held protests. They would walk out of class to protest on our track.

RHS students attended youth summits on race held at area colleges such as Harris-Stowe College and Washington University, as well as at neighboring high schools.

The governor came several times to our district to discuss the impact these events had on teens.

St. Ann’s Police Chief wanted to be interviewed by our students so he could explain his officers’ viewpoints. His police staff was getting pushback due to the content of one of his officer’s social media accounts. His officers were also manning the front line of Ferguson.

Due to the initial conflict and the grand jury verdict in the Michael Brown case (that meant no charges would be filed against Darren Wilson), the impact on our city was continuous and immeasurable. This topic did not go away.

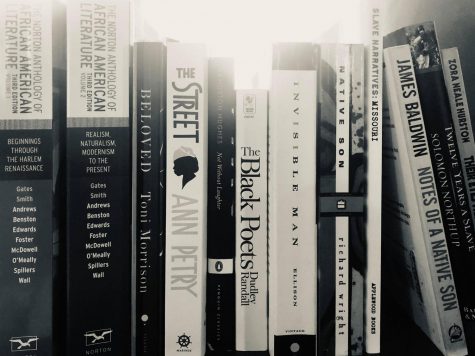

America’s racial indifferences can be scary for many advisers and student journalists to tackle, but journalism is about documenting history. High school journalism is respected for giving a voice to the local population and humanizing the important issues. I heard that message loud and clear during the 2019 JEA/NSPA Fall National High School Convention in Washington, D.C.

Now, we face global protests over the killing of George Floyd, Jr. in Minneapolis. As the BLM movement gains even more voices, it is critical that our students not shy away from reporting on this topic.

Since my students and I have already experienced this type of reporting, we have some insight on how to go about it. Here are a few steps we went through in reporting:

-

Check your own racial biases and beliefs.

Bias was important to consider when we were having discussions with people who did or did not look like us. RHS is the second-most racially diverse high school in Missouri, yet we never had an understanding of what everyone was going through. We discussed white privilege extensively using the Courageous Conversations Model. There are several bias checking articles to help you work through those steps to help it be less teacher led and more student directed.

This is another helpful resource: You May Be Biased and Not Know It (and Here’s How to Check)

-

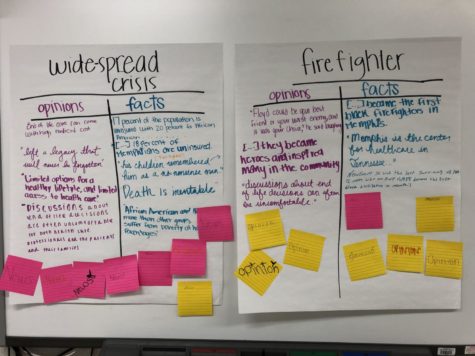

Use the local and/or school data.

We know that numbers are facts that can’t be disputed. It is the truth, you can build off of it for strong storytelling.

See this example in the 2020 Robert F. Kennedy High School Journalism Award winner who used data to support disparities in equity in education in their school Black Students Nearly Two Times as Likely to be Suspended as White Peers in the ICCSD.

-

Allow the voices from the youth to be your guide.

Sharing real thoughts and feelings can help in understanding why your community is the way it is. Singular stories can build bridges towards empathy.

Our high school media program worked with Gateway2Change Youth Summit to gather students from across the city of St. Louis City and St. Louis County to discuss race and document the students’ voices. Having a guiding question for what your community wants to learn makes the conversations stay focused.

What did we believe before the protest? What do we believe now? What is our future because of this?

Here are two helpful links:

-

Interview all parties involved. Everyone has a voice.

Police officers’ voices are just as important as the protestors. We also interviewed students in schools that are majority white, as well as schools where the majority are minority. Yes, we talked to students from other schools, not just RHS. We also talked with business owners who had cleaned up after looting. The more inclusive you are at storytelling, the smaller the chance of biased reporting.

Here are examples of reporting that covers many sides:

- KRHS TV News: Special Edition on St. Louis Protest

- Podcast: “What is Ritenour Made of?” A podcast on Diversity at Ritenour High School

- Living Hispanic in America – 2018 JEA 3rd place Podcast Pacemaker Award

- Soldan/Parkway Sister Exchange

-

Look for professionals to help with your work.

The RHS journalism program brought in professional journalists from the St. Louis area who had been researching and reporting on both educational and racial issues. Not only was this a chance to be educated, it reinforced that our students were doing real work. That makes a big impact on the level of care and concern students put into their reporting.

We weren’t just practicing to be reporters, we were reporters! With that newfound confidence, students created quality journalistic content at a much faster rate than on any other topic covered previously.

-

Help students find and use their voices to report on a topic they may not be comfortable with at first.

I was privileged to sit in on a session with directors Sabaah Folayan and Damon Davis of the documentary “Whose Streets?” The directors asked a young white college freshman journalism student what she was feeling after the movie. She was very quiet and apprehensive to speak. She stated, “I just don’t know how I can be the one to talk about this topic as a journalist.”

But if not her, then who?

According to the Census Bureau, racial and ethnic minorities comprise almost 40 percent of the US population, yet they make up less than 17 percent of newsroom staff at print and online publications and only 13 percent of newspaper leadership.

I know talking about topics foreign to us is tough, but we don’t get to pick or choose what is news. The news is not always white America issues. It is also made up of stories about diversity, poverty, and police brutality. With a largely underrepresented newsroom of minority voices, we need to become true journalists who hear and report on topics that impact ALL Americans.

-

Be prepared to face your fears while becoming a better teacher throughout the process.

The whole time I worked with my students I was scared. We had some threats made to our principal. I had a couple of pro-police online commenters call out our level of bias. No doubt I had friendships that changed. But, I also became a better teacher. I got stronger as the student work became richer in its depth. In the end, I had administration support for tackling a tough subject and giving the district credibility for tackling racial issues. Our program was even highlighted in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

In conclusion, I can’t tell you how reporting on these issues will go over in your community. Just know that this is not going to go away. The fight for social justice and true equality will not stop anytime soon. Your students deserve the opportunity to report on these issues.