A Q&A with the experts

News and media literacy aren’t the easiest of topics to wrap your head around. To help you ease your way into the field, we’ve asked the experts some questions that might make the topic a bit simpler to grasp. We also wish to thank them now for their thoughtful responses.

Clark Bell, Journalism Program Director at the Robert R. McCormick Foundation

Kelly Furnas, Executive Director at Journalism Education Association

Alan Miller, President and CEO of The News Literacy Project

Dean Miller, Director of The Center for News Literacy

Eric Newton, Senior Adviser to the President at The Knight Foundation

1) How do you define news literacy?

Clark Bell: News literacy is the ability to use critical thinking skills to judge the reliability and credibility of news reports and information sources. It enables citizens to become smarter consumers and creators of fact-based information. It helps them develop informed perspectives and the navigational skills to become effective citizens in a digitally connected society. News literacy programs also emphasize the importance of news and information, the value of reliable sources and appreciation of First Amendment freedoms.

Kelly Furnas: The term can be incredibly nuanced, but in the broadest terms, news literacy is the skill of seeking out, consuming and interpreting the news.

Alan Miller: News literacy is the ability to discern and create credible news and information across all media and platforms as a student, consumer and citizen. It is also intended to foster an appreciation of quality journalism.

Dean Miller: “News Literacy is the ability to use critical thinking skills to judge the reliability and credibility of news reports, whether they come via print, television, radio or internet.” – Howard Schneider, creator of the first News Literacy course (2006) and founding director of the first and only academic center dedicated to development and dissemination of News Literacy materials (2007).

Eric Newton: News literacy helps people separate fact from fiction within current events coverage. It’s content oriented, specifically, non-fiction content.

2) What is the relationship between news literacy, media literacy, digital literacy, information literacy and civic literacy?

Clark Bell: All intersect and/or intertwine with the ability to read and write. Think of news literacy as the spine of knowledge, as it helps develop the intellectual depth and critical skills necessary to question and analyze. It is the basic nerve center of learning. Stretching the anatomical analogy, civic literacy is the heart, information literacy the eyes and ears and digital literacy the arms and legs of 21st Century knowledge.

Moreover, news literacy is critical to the process of engagement in a democratic society. It helps connect information and civic literacies. In a society where much of the news and information is consumed online, digital literacy overlaps news literacy.

In summary, news literacy deals specifically with using an inquiry-based approach to consume information. The information is then applied to public life through effective communication and contributions to constructive civic discourse.

Kelly Furnas: All literacy skills are related because they deal with a person’s ability to consume information. And while there is some overlap in learning how to process messages, news literacy stands out because it directly affects a person’s ability to become make decisions about the community in which they live — whether that community be a town, state, country or inter-connected world. It also is a critically important skill for producers of news, who need to understand how their messages will be interpreted by their audiences.

Alan Miller: News literacy is a specific focus within the larger field of media literacy. It uses the standards of quality journalism to give people the critical-thinking skills to know when to believe a piece of information as the basis for their decisions and actions.

Media literacy is a broader and more general approach to media consumption that encourages consumers to analyze all media content, including popular entertainment. Media literacy puts more emphasis on the social and political origins and potential impact of a piece of information.

Digital literacy, information literacy and civic literacy are all related subjects that overlap news literacy in various ways. Each represents a set of skills intended to raise awareness.

Digital literacy, which is sometimes called “digital citizenship,” concentrates on issues raised by digital communities and communications. Digital literacy practitioners seek to raise awareness about appropriate online conduct and the pitfalls of digital media, including the misuse of digital imagery, cyber-bullying, the potential impact of information posted on the Internet, and the importance of one’s online reputation. News literacy also seeks to make people aware of the challenges created by digital media, making these two skills sets closely related and mutually reinforcing.

Information literacy tends to be practiced by those trained in information or library sciences: the ability to locate information for a specific purpose. Since becoming information literate also involves evaluating the importance and credibility of information once it is found, this area is well-aligned with the core focus of news literacy.

Civic literacy adjoins news literacy in still another way. Civic literacy is intended to inform citizens about civic institutions and to increase citizens’ engagement and participation in a democracy. This mission is closely related to two core assumptions of news literacy: that information is the basis for the decisions and actions of citizens and, consequently, that a free and independent press that serves the public interest plays a vital role in a robust democracy.

Dean Miller: I think of Media Literacy as addressing the broadest scope: encompassing entertainment, advertising, news, advocacy, social media and media effects theory, etc. It is the legacy discipline and we are grateful for the work of generations of scholars who organized critiques of story-telling that go back thousands of years. The rest of these literacies, including News Literacy, I think of as subsets of Media Literacy.

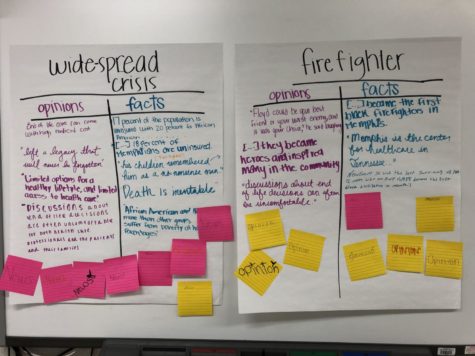

News Literacy focuses narrowly on the critical thinking skills the individual needs in order to find the reliable higher-quality journalism that is necessary for them to fully inhabit their role in a democracy. Once we’ve taught students to “know your information neighborhood,” we make no bones about the fact we’re spending the rest of the semester drilling down on journalism.

Eric Newton: News literacy focuses on the integrity of news content; media literacy, understanding and creating anything in media; digital literacy, skills needed to work in and navigate cyberspace; information literacy, the same analytical and creation skills applied to information of any kind, and civic literacy, understanding how government works and how to participate in it. Obviously they overlap.

Knowing what quality news and information is, the type that helps you run your community and your life, doesn’t get you far if you don’t know how to navigate cyberspace and use the latest digital tools.

Some bundle all these together as “21st century literacies” but those would also include “literacy,” the ability to read and write and understand what others are saying, and “numeracy,” the ability to reason with numbers.

3) What are some of the biggest challenges in cultivating news literacy in the digital age?

Clark Bell: NOISE!!! is the most formidable challenge. Students are overwhelmed by the sheer volume of information received every minute of every hour of every day. That makes it extremely difficult to become a discerning consumer of news.

The slashing of newsroom budgets equates to smaller newsroom, watered down content and lack of faith in the quality of news produced.

These two factors result in an increasing number younger people who depend on social networks for news and information. Say what you will about legacy media, but at least the stories are vetted and edited.

Kelly Furnas: Perhaps the best practice for fostering understanding of news literacy is providing students the opportunity to digest news from multiple sources, and then promoting a healthy discussion about how those reports compare with regard to production, language, representation and intended audience. Unfortunately, students today are being asked to do so much in such a limited amount of time, that the simple acts of reading and watching the news are often luxuries in secondary education.

Alan Miller: By radically disrupting the way people access, consume, create and engage with information, the digital age has exponentially increased the need for news literacy. People now have incredible amounts of news and information literally at their fingertips. But this explosion of sources of information of greatly varying credibility, accountability and transparency, has also created the need for everyone to learn to think like journalists.

This process has greatly democratized the flow of information, essentially putting the audience in charge. It has also created widespread mistrust of any person or organization that seeks to control information in any way, whether to censor, repress and conceal or filter, mediate and curate.

While much of this new expectation of unfettered access is positive, it has also exacerbated the amount of cynicism about journalists and news organizations. The assumption that any filtering of information is inherently agenda-driven appears to be gaining growing traction.

The explosion of information has also introduced significant challenges for advocates of news literacy. This access to a much broader range of information (including a significant amount of misinformation) has enabled people to indulge and confirm their own biases by seeking confirmation rather than information. This, in turn, has often results in suspicion about news sources that do not provide this affirmation.

Dean Miller: Two things:

First: Among our leaders, a lot of time is lost to the tendency of each generation to think their challenge is unique. Aileen Estrada Fernandez, a media scholar at Universidad del Sagrado Corazon/ Puerto Rico, says it best: “…education for critical media interpretation has its foundation in the notions of the public debate that arose in ancient Greece, after the Greco-Persian wars.”

That parental task, teaching citizens to think critically about information before they leap to conclusions, has not changed in eons. We need to spend less time demonizing new technologies and more time installing the BS-detector apps that went viral when Plato and his peers codified rhetoric and logic and ethics into a syllabus of workable lessons.

Second: Among students, a lot of time is lost to the tendency to think their generation’s good intentions are unique. Until they recognize the web’s culture of anonymity as the equivalent of the conjurer’s smoke screen, they’ll be duped by professional-looking hokum that anyone can produce on almost any mobile device.

Eric Newton: Understanding that the definition of news is changing in the digital age. Using digital tools and techniques to teach.

4) What are the best educational practices at the secondary school level to foster an understanding of news literacy and encourage civic engagement?

Clark Bell:

(a) Relevance: curriculum and “art” of teaching must connect to things that are meaningful in students’ lives.

(b) Integration: curriculum that is connected to a larger continuum of learning. Teachers from different courses who collaborate and partner with peers.

(c) Provides insight: students respond to information that answers the “SO WHAT” question. That type of learning will spark students to respond and take action that can impact their communities.

Kelly Furnas: Perhaps the best practice for fostering understanding of news literacy is providing students the opportunity to digest news from multiple sources, and then promoting a healthy discussion about how those reports compare with regard to production, language, representation and intended audience. Unfortunately, students today are being asked to do so much in such a limited amount of time, that the simple acts of reading and watching the news are often luxuries in secondary education.

Alan Miller: No one likes to be deceived, certainly not young people. Building news literacy lessons and other content around examples of information and issues that directly impact their lives is the most effective way to make young people realize the importance of news literacy. A related practice that works well with any audience, including students, is to begin by determining what kinds of decisions that an audience makes based on news and information and using this to build lessons and discussion opportunities.

Dean Miller: We know from several studies of the thousands of students who take News Literacy at Stony Brook that they score higher on civic knowledge quizzes than do their peers. They are more likely to register and vote.

In other words, teaching News Literacy increases civic engagement. Reliable information is the lifeblood of democracy, so once you teach students to tell the difference, they are ready to engage with self-governance and they do.

Eric Newton: I don’t think it’s a best practice to isolate news literacy from the other forms of literacy.

5) Other comments?

Alan Miller: We welcome the participation of ASNE and its members to this mission.

Dean Miller: There’s a big difference between people who are committed to the discipline of News Literacy and those who merely borrow the name. We share our materials promiscuously in hopes of fostering the kind of innovation and diversity you now see in News Literacy courses at more than 50 campuses nationwide and in almost a dozen countries overseas. So we’re certainly inclusive. If you’re teaching critical thinking to news users, with news as the daily text of the course in which you demonstrate methods for analysis of evidence, sources and fairness, I respect you as a colleague. But if you just slap the News Literacy label on an old-line media literacy or scholastic journalism program, you’re suffering an irony deficiency, or you haven’t read anything about News Literacy.

Eric Newton: Communicator, message, medium and community all are equally important. They represent the value chain of communication. That means something that some journalists find difficult to accept. News is not more important than technology, nor the other way around; they are both necessary components. A good news story without a medium or a community involved is a tree falling in the forest with no one there to hear it.